Film begins in 1895, when female workers exit the factory and walk in front of their employers’ camera, pacing the space of the frame quickly to keep up with the reel’s running time. “It’s the invention of a new physics, operating by the pressure of time spans on the body, by the condensation of space within the frames”: the act of producing new rhythms for new bodies. Cinema is to do with representation, but also with a “morphological inflection, resulting from the meeting between the rotating metal teeth of a machine, the reaction time of silver salt and the body of a worker.”1

The present exhibition reflects on another projection machine, whose history and consequences, unlike cinema, are circumscribed by national boundaries, specific histories, and ideological configurations. The regime of production and representation of socialist realism radicalizes the violence that the creation of a new image does to its subject: it intensifies the fraught relation between refashioned representation and that which is represented. Its insistence on a particular, projective notion of reality is commensurate with the coercion of daily – cultural, social, emotional – life into a grid whose perspective lines and vanishing points carry heavy ideological charges. It enforces what it represents onto that which it represents, so that representation would replace reality.

Regardless of differences between national variants, the main ones being propagandistic intensity and iconographic proliferation, socialist realism glorifies labor, and – directly or obliquely – the power in whose service labor toils. To return to the project’s title, workers are symbolically locked up in the factory, fabricating, hammering away, chiseling and polishing new realities: an exit from history through communism’s triumph. Artists, on the other hand, leave the studio and immerse themselves in this social landscape of permanent productivity (or, alternately read, in a brutal world of faceless collectivism), both capturing and visually formulating the process.

This exhibition is an attempt to articulate specific fragments of the collection at the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana and contemporary art projects whose concerns revolve around the notion of realism. It works through two hypotheses about the realism of socialist times, the two ways in which that discourse did not end. The heroic drive in those images, banishing metaphor but having it return as Freudian slip, undermines and corrodes their realist aspirations, and deflates the mimesis of a world “to come.” On the other hand, the relations between artistic freedom and political subservience that underpin socialist realist art production radicalize an equation that contemporary engaged practices must also respond to, even if within a different regime of political interlocution.

Socialist realism did not prevail over art-historical conventions, while the political complicities that propelled it might have something to say about – and to – contemporary art at large, bring a corrective to its claims of emancipation and engagement. Though often disavowed as naive within artistic discourse, the relation between visual language and economic and political hegemonies as constantly emphasized in socialist realism remains a fact to this day, in spite of the many continually renewed claims to art’s autonomy; an autonomy that can only be maintained precisely because of the economic and political structures that profit from art’s image as autonomous. Socialist Realist art was never able to internalize the revolutionary changes in political and social life it was expected to depict, nor was it able to withstand that shock wave of liberalization that obliterated them. A social realist art “to come” is a renewed articulation of the links between art and politics, between the impossibility of art’s autonomy and the impossibility of its impotence. Here are some examples.

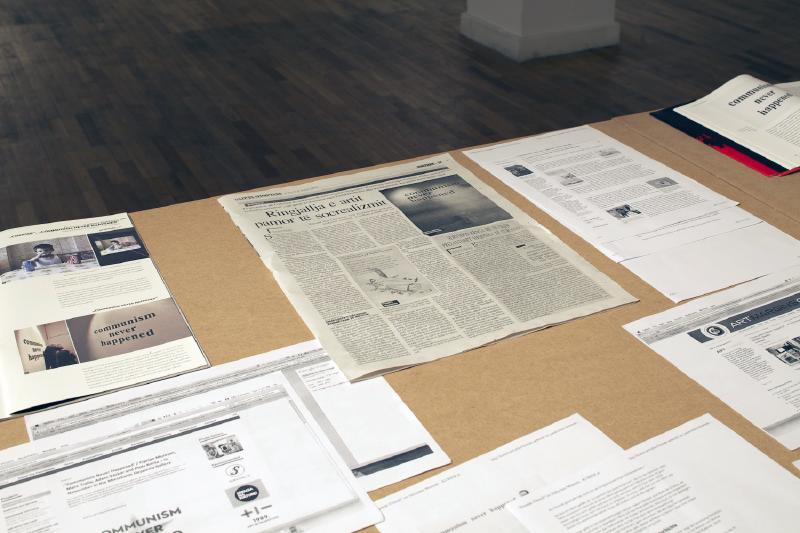

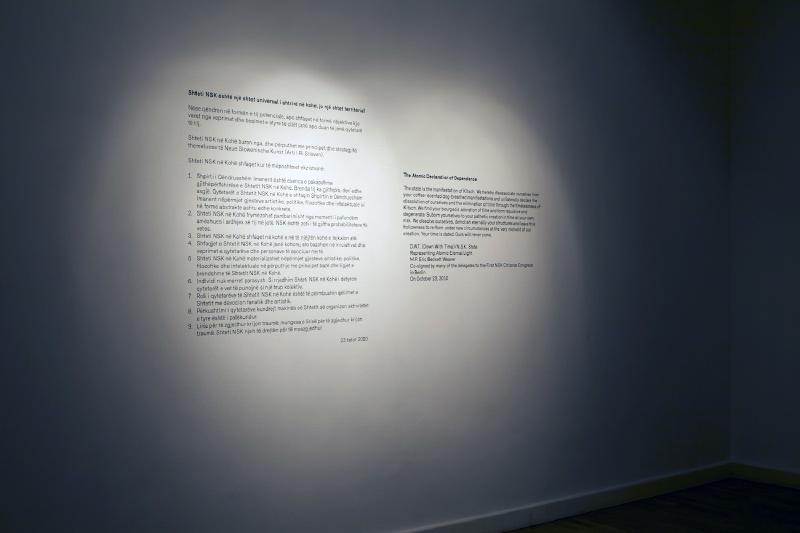

Curated by Mihnea Mircan with Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei. National Gallery of Art, Tirana, Albania, 2015. Contributing artists: IRWIN, Armando Lulaj, Ciprian Mureşan, Santiago Sierra, Jonas Staal, and Sarah Vanagt. Documentation by Marco Mazzi. With financial support by the Prins Claus Fonds.

An open-access exhibition catalog was published by punctum books with contributions by Mihnea Mircan, Raino Isto, Jonas Staal, Suzana Varvarica Kuka, Inke Arns, Sarah Vanagt & Tobias Hering, Alban Hajdinaj, and Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei.

-

Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, notes on their multi-part video project The Unmanned, 2009–ongoing. ↩︎